'The gym bros all have eating disorders': OK, now what?

Most social media content about eating disorders in men isn't helpful. Here's what could be.

Thanks for reading Body Type. If you like this post, please share it. And join my subscriber chat here to talk all things body image with me.

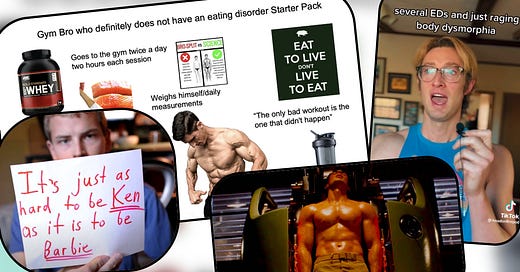

As a 10-second aside in a TikTok about the sexual politics of men wearing “pump covers” in the gym (I can’t get into it, God help me, just watch the video), TikToker Don says, “…most of these ‘muscle bros’ have several [eating disorders] and just raging body dysmorphia.”

Most eating disorder content aimed at women feels like it’s for them: It’s empathetic, supportive, and imbued with solidarity. But most content about eating disorders in men feels like it’s about them: It’s glib, flippant, and positions the creator above the issue, looking down.

“All the gym bros have eating disorders” is huge in gym culture discourse lately. It’s become something to say to demonstrate alignment with the zeitgeist no matter whether you get your hands dirty in the issue and its solutions. It’s become something to say that might feel like activism but is usually nothing.

Also huge lately is #GymCreeps discourse, which Casey Johnston wrote about here:

“Posting about the creepy or boorish behavior of other people at gyms has become one of the surest ways to go viral, especially on platforms with algorithms that never let reality get in the way of a good old-fashioned outrage cycle.”

This is how “all the gym bros have E.D.s” content feels. Most people aren’t posting about gym bros with E.D.s to meaningfully examine the why, or to offer the same support we do to women or trans or nonbinary people — they’re posting about gym bros with E.D.s as if to call them out for bad or foolish behavior.

I’m sure some content creators think they’re shedding light on an important issue. But when they broach this topic as a quippy aside or a meme, it’s clear that their foremost intention is to do numbers, because people love to hate gym bros and the men who dare to join their ranks.

I ask: So you made a funny little video dunking on some guy in a tank top who you say definitely has orthorexia. Did you get the views, did you get the clicks? Now, do you actually care enough about men with eating disorders to do anything else?

One in three people with an eating disorder is male and rates are rising globally. Focusing only on men who make disordered eating behaviors visible — because yes, posting about not seasoning chicken for fear of the calories is a red flag — perpetuates the idea that gym bros are the exclusive class of men who struggle. Many E.D.s are “invisible,” under-diagnosed, and atypical; many people you see in the gym are not grappling with E.D.s and many of the people in the world you’re not paying attention to are. What’s so vexing about disordered eating is that it can be a case of “maybe, maybe not,” and “it depends.” Disorders are marked by dysfunction, distress, and deviance, and these fall on a spectrum for everyone. Does someone who goes to the gym five times a week and tracks his protein intake have an eating disorder? Maybe. Maybe not. It depends.

Since I’m not an eating disorder specialist or clinician, I’m not in the business of diagnosing other people. While we can recognize red flags, it ultimately doesn’t serve anyone to speculate about the potential disorders of someone we don’t know just because we saw them measuring oatmeal on Instagram. But we know that plenty of men in general have eating disorders because of what the data tell us. If we’re going to discuss a subset of such men — the gym bros — we must consider what drives the issue for them, just as we do when it comes to women.

The most obvious contributing factor is popular culture. As Raquel S. Benedict puts it in her inimitable piece, “Everyone Is Beautiful and No One is Horny”:

“Actors are more physically perfect than ever: impossibly lean, shockingly muscular, with magnificently coiffed hair, high cheekbones, impeccable surgical enhancements, and flawless skin, all displayed in form-fitting superhero costumes with the obligatory shirtless scene thrown in to show off shredded abs and rippling pecs.”

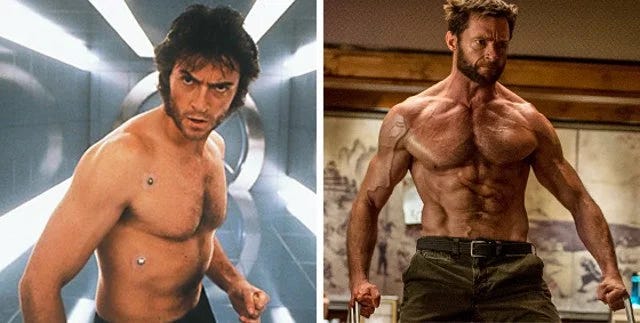

The classic example is Hugh Jackman’s physical transformation playing Wolverine — first in 2000 when he was in his early 30s, then in 2017 when he was almost 50.

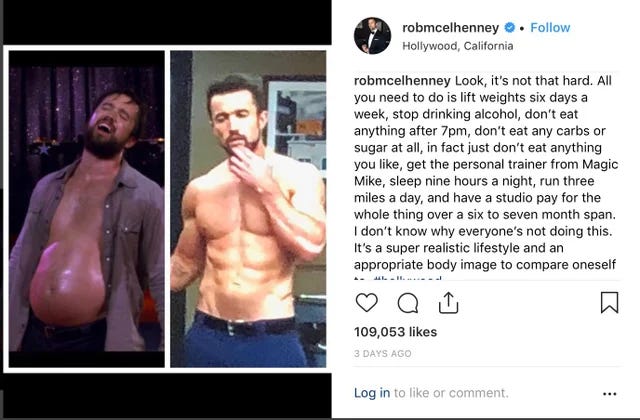

The rational person knows that Hugh can only maintain that physique (temporarily, while filming) because he’s got the best trainers, dieticians, and performance-enhancing substances money can buy and a multimillion-dollar incentive to do it. That doesn’t make getting low single-digit body fat easy, even for the modern celebrity. Zac Efron talked about it post-“Baywatch,” and Rob McElhenney posted about it in 2018: Staying this lean and jacked is typically a miserable experience.

But we’re so accustomed to this male physical ideal that when Jason Momoa looks like this but doesn’t have his “Aquaman” eight-pack, he’s said to have a “dad bod.” When Tenoch Huerta, who looks like this, has a nice, big ol’ powerlifter back, there’s still some freak waiting bare-assed in the wings to say it’s not cut up enough.

A guy might take this all in and think, “If Hugh Jackman can do it at 50, I can do it at 26 — if I don’t, someone will say I have a dad bod.” As a woman who came of age at a time when Jessica Simpson was shamed into agoraphobia for being a size four and so trying and failing to be skinny was all that mattered to me, I don’t see the men chasing a twisted physical ideal as vapid lunkheads. I see them as mired in the same body image hell I’ve been in most of my life.

Raquel continues in the “Horny” piece:

“[In the past] solitary exercise at the gym also had a social, rather than moral, purpose. People worked out to look hot so they could attract other hot people and fuck them. Whatever the ethos behind it, the ultimate goal was pleasure. Not so today. Now, we are perfect islands of emotional self-reliance, and it is seen as embarrassing and co-dependent to want to be touched.”

What Raquel calls “rigidly isolated self improvement” also contributes, I think, to the rise in male E.D.s: The more lonely, isolated, and bought into total self-reliance men are, the more likely it seems that they’d turn to obsessive exercise as a means of self-improvement and fall victim to issues like “bigorexia” in the process.

I imagine that a guy is likely to feel even more isolated, withdrawn, and defensive if he’s got a slew of internet randos coming for the lifestyle he values with an armchair diagnosis, meme, or insult. The people who could actually get through to gym bros who are struggling won’t be women stitching their TikToks to tell them to go to therapy or a guy on YouTube calling the gym stupid. The people who could actually get through to them are other men who go to the gym.

Ben Carpenter is a trainer I first found in a video about how staying extremely lean sucks — which he’d know as a former fitness model. He’s made videos about his eating disorder story, about how the leanest people often have the worst advice, and about how his leanness is due in part to his Crohn's disease. He’s one of the most candid, empathetic, and no-bullshit fitness professionals out there. He’s also got the kind of physique a lot of gym bros are chasing.

Most people aren’t going to listen to anyone who they don’t think gets it. A lot of men exercise to look something like Ben, so Ben is who they should be hearing from because he cares about fitness and is attuned to the potential risks of training. He’s the kind of creator who could help men understand that they can add some muscle, cut some fat, and look buff in a tank top but must do so in a sane, safe, sustainable way lest they end up in the same position Ben once found himself.

Gym bros should be paying attention to the Bens of the social media world; or guys like strength training coach Jordan Syatt, who’s posted about how a higher body fat percentage made him happier and how being shredded is overrated; or nutrition coach Marcus Kain, who talks about binge eating disorder and body image on his podcast “Strong Not Starving.” For every bodybuilder’s Instagram the gym bros follow, they should see if he’s made a YouTube video about his eating disorder experience — many of them have. If you’re going to get into this lifestyle, the bodybuilders seem to say, know what you’re getting into.

Also helpful are the dudes demonstrating how deceiving fitness content can be, like this guy, who should be awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom as far as I’m concerned. In the same vein*, here’s a brain-busting screenshot from Jeff Nippard’s excellent video, “The Ugly Truth About Getting Shredded”:

Our pal Ben has done a great video on deceiving lighting, too.

As I’ve written, women fitness influencers make a lot of this kind of “body honesty” content, and I think it’s largely positive that they do, even if it’s kind of annoying because their bodies are typically the most socially accepted type:

“When it’s clear just how harmful Instagram is for young women, I’d argue that fitfluencers actually have a responsibility to make these kind of posts. If their accounts are going to exist, this is a crumb of harm reduction we might reasonably expect from them. These posts shouldn’t be celebrated or confused for a display of bravery. They should be considered representative of a bare minimum principle: Don’t bullshit people at the expense of their mental health.”

I’d love to see more of this kind of content from the bros, too.

The next time you come across flippant “all the gym bros have E.D.s” content, ask yourself if most people on social media are creating the conditions for those who are struggling to self-reflect and help themselves. Ask whether this content is likely to make men at risk of eating disorders withdraw or get defensive because they feel accused of deviant behavior or made the butt of a joke. Ask whether the content you’re seeing is really addressing an issue, or just meme-ifying it.

Then, maybe share instead the content that’s probably less likely to go viral, but more likely to matter to someone who needs it.

Great post. Would be interested is reading more about male experiences on this topic, and in particular gay male experiences which can be more extreme.

Because it is guys, nobody but a hand full of "men's corner" influencers will care. Not even most men. It would be great if they became nudists and learned about body neutrality and body acceptance. Doing my bit on my own substack..