‘The Whale,’ reviewed by a binge eater

An eating disorder story that barely scratches the surface.

Spoilers and descriptions of disordered eating abound.

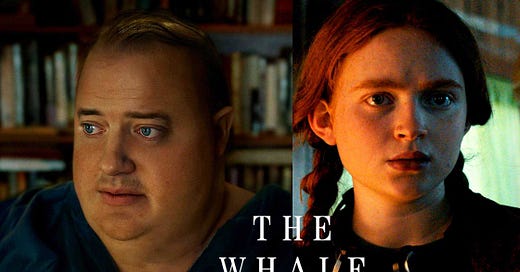

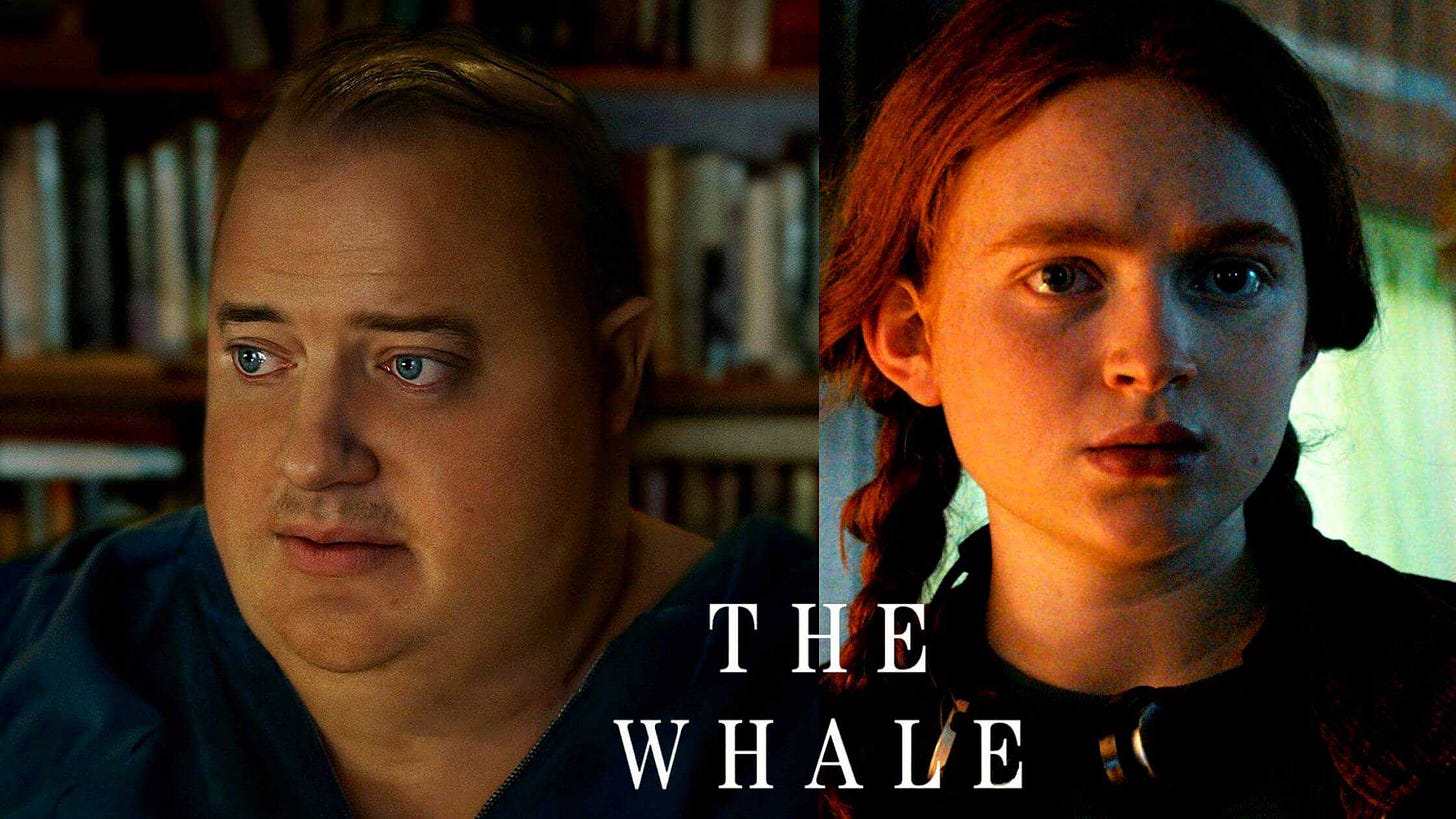

Now that I’ve seen the Darren Aronofsky-directed film “The Whale,” starring Brendan Fraser and based on the Samuel D. Hunter play, I return to this tweet from the largely infuriated discourse about it:

The idea that any eating scene in this film — about a grieving and reclusive 600-pound man named Charlie — demonstrates excitement in a “Yay, I’m so happy to be eating this!” way is unthinkable to me. Fraser portrays a man living with a debilitating binge eating disorder. Hunter has experienced eating issues himself: “My depression manifested physically as I self-medicated with food,” he said. Binge eating disorder is not exciting, it’s desperate and frantic. It’s hardly comedic fodder. It’s a fucking prison.

I’m glad for this cinematic attempt to portray it, even if it’s not perfect.

People who have never been fat will see “The Whale” differently from fat people. People who are 400-plus pounds will see it differently from people who are 275 pounds. And I see it how I do because I, like Charlie, have dealt with binge eating disorder for much of my life.

The eating disorder element of “The Whale” has been overshadowed by people’s anger about other things: that Fraser wore a fat suit, how Charlie’s body is shown on screen, and what they think the film says about fat people in general.

From Coleman Spilde in The Daily Beast:

“Aronofsky’s direction takes glee in the film’s makeup-by-magic approach, lingering on full-body shots of Charlie as if to force the viewer to confront whatever prejudices we have … [it] pores over Charlie’s size with offensive voyeurism.”

Should we not see our protagonist? Should we not watch the resultant challenges of Charlie’s disorder play out because they’re difficult to watch? Rue drools all over herself for minutes as she detoxes in “Euphoria” and it’s not offensive voyeurism, but Charlie’s naked body in the shower is? Isn’t the true offense here the idea that lingering shots of a struggling fat body are more offensive?

Roxane Gay wrote for The New York Times that “the onscreen portrayal of fatness bears little resemblance to the lived experiences of fat people.” Fat people, like everyone, have all kinds of lived experiences. There are fat people who do not live like Charlie and fat people who do. But neither assertion matters when the viewer takes the film as intended: This is only one story. Charlie’s story.

The ire is understandable, though. As the cultural tides shift from “everyone should be thin” to “people of various body sizes should be treated with respect and can be happy and healthy,” a Tragic Fat Person movie can feel tiresome. But even as body acceptance messaging surges into the mainstream, there still are and will always be fat people for whom aspects of life are more difficult because of their fatness. I was one of them, even though I was never anywhere near Charlie’s size. Some people feel “The Whale” is cruel, is punching down. That’s not my read. It’s not punching. It’s showing. But a lot of people won’t see this film, and all they’ll hear is that Brendan Fraser wears a fat suit in some movie called “The Whale” (get it?) and eats a lot and has a sad life. Nothing more to see or learn or think about here!

But what if the sadness of “The Whale” was interwoven with a more robust, clear, and meaningful examination of the nuances of Charlie’s disordered eating and the reviews of the film uplifted that? I think we’d have a better and more important film on our hands. Showing the wreckage of an eating disorder is as artistically valid as showing the wreckage of substance abuse or any other kind of self-destructive behavior, but it has to be done well. “The Whale” just barely scratches the surface.

At one point, Charlie’s estranged daughter Ellie asks him why he gained so much weight. Charlie explains that his partner died and he didn’t handle it well. That’s about all we get as far as his interiority about his disorder. In a world where binge eating disorder is so common yet so misunderstood — it’s often overlooked, but three times more common than anorexia and bulimia combined — there’s a missed opportunity here. Why not some dialogue from Charlie about his emotional state, how food came to play this role in his life, why he might feel trapped by it? Why not have the film pull from what Fraser himself did to prepare for the role?

He spoke with people who live with eating disorders:

“They were open-hearted in telling me how they came to the point in their lives where they were so heavy they were bedridden. The common denominator was that someone spoke cruelly to them when they were very young.”

God, where’s that dialogue? How I wish Charlie could be so open-hearted to his daughter, allowing her and the audience to gain further insight and empathy. How I wish Charlie had more space to describe his pain and thoughts.

In a scene following an interaction that unnerves him, Charlie tears through his kitchen, eating everything on hand. Gay in her Times review called this scene “unnecessary.” I fail to understand how showing a binge episode in a movie about someone with binge eating disorder is unnecessary. Is it unnecessary because it’s gross and shocking and a little scary? My friends, that’s what the disorder is.

Charlie eats lunch meat and chocolate together and dumps mayo onto pizza. There’s little gastronomic sense to his binge. This is familiar. In my worst binges, food ceased to have any sensation on my palate beyond sheer volume. But I don’t see a gag or a sideshow character in the scene. I see the same coping mechanism I’ve used in the worst moments of my life. I find it entirely necessary to see those moments of total breakdown I’ve had represented on screen because then, they’re less in the shadows. I suppose I feel somehow less alone.

Other coping mechanisms besides Charlie’s binging are also shown in “The Whale”: Charlie’s ex-wife is an alcoholic. One character says he had a “problem” with smoking pot too much. Everyone in this film is dealing with some serious shit. But Charlie wears his coping mechanism perpetually on his body. That can be a hard way to live, and a lot of people can relate. I think creators should continue to make art about it, and I hope how “The Whale” falls short will encourage them to pick up the mantle.

From Barry Levitt in The Daily Beast:

“The film’s portrayal of size is deeply humanistic and is more of an expression of how disorders can take over and dominate our lives … The Whale’s tremendously powerful binge scene exemplifies The Whale as its most human, even if it’s also at its most exploitative.”

“The Whale” does not dehumanize Charlie because he’s fat and lives a difficult life and we can see that. But it doesn’t offer up enough of his humanness. It doesn’t offer us enough of his mind. And so we may be left with what Christy Lemire wrote in her review: “The message The Whale sends us home with seems to be: Thank God that’s not us.”

If “The Whale” offered a more detailed and nuanced view of how Charlie specifically is wrestling with and thinking about the same issue as millions of people, of how binge eating disorder can so easily come to dominate one’s life, maybe audiences would leave thinking not, “Thank God that’s not us,” but rather, “That could be any of us.”

Ooooooh your last line is key.

I'm also perplexed by how many reviewers aren't taking into account Aronofsky's oeuvre. Requiem for a Dream: the prostitutes at an office party scene? Unnecessary and exploitative? showing an overhead of Jared Leto in the anatomical position, but with a mangled arm? unnecessary and exploitative? I find Aronofsky movies difficult to watch, but not because they're bad. Because they're unflinching.

I have not seen The Whale and truthfully it will probably be the first Aronofsky film I don't see. But, your review is incredibly thoughtful, bjective and generous given what you share about your own experience. If I do decide to watch it despite what seems like pretty big shortcomings, I will be considering what you've written and shared in your review.