Thanks for being here! Note: I’m not putting anything behind a paywall right now because I want to reach as many people as possible. Body Type is a one-woman show and a side gig, though, so paid subscriptions help me keep the lights on. If you like what I do, upgrading for $5/month, or $50/year (which = ~$4 a month!) is a vote of support I so appreciate. If you want to essentially tip me for my work, click here:

(If you’re already subscribed for free, click on “✓ Subscribed” and then change your subscription plan to a paid one when the “Manage your subscription” page pops up.)

Also: I wrote a piece for Dazed magazine. Check it out here.

Until I was around 25 it was clear the kind of woman I was supposed to be: One who was thin or trying to become thin. There were no other realistic or acceptable options I knew of, because I’m an American, middle-class, white, millennial woman who was a teenager in the early 2000s.

My mother and hers before her had suffered under the same thinness mandate. In this regard, millennials like me weren’t special. But how we received it, and the sheer volume of messages we saw about our bodies, changed the game. Many of us were hitting puberty during the peak of girl-centric magazine publishing (Seventeen, Teen Vogue, CosmoGirl), and an expanding cable TV landscape with programming precisely targeted to us. And of course, we had the internet.

By 2006 MySpace was the most-visited website on the planet, until Facebook took the top spot in 2008. Gossipy websites that routinely called famous women fat (Perez Hilton et al.) started around 2004, joining forces with celeb rags that plastered things like “Stars lose fight with CELLULITE” on their covers. Tumblr started in 2007, and its pro-ana spaces were in full force by 2011. For other 35-year-olds like me, that means that from the time we were around 12, it wasn’t only the people we knew who were reinforcing that thinness was next to godliness — it was also the triad of print, broadcast, and digital media that was taking over our lives.

In that way, we were kind of special.

It was all Not Our Mothers’ Body Anxiety for another reason, too: We saw content calibrated to make us insecure right alongside content encouraging us to be less insecure. As

explains about research on girl-centric print media done by scholars Leslie Winfield Ballentine and Jennifer Paff Ogle:“… there was an abundance of articles introducing something that the reader should be worried about (cellulite, wrinkles, blemishes, bacne, “flabby” areas, stretch marks, “unwanted” hair, body odor) and how to address it in order to achieve the “ideal” body….but also, often in the same issue, there were articles instructing the reader to let go of others’ ideas about what beauty or perfection might look like.”

At adolescence, with self-esteem fragile as moths’ wings, women of my generation were positioned at the business end of a firehose of innovations in self-loathing coupled with the clashing directive to love ourselves. We were made to feel we had a choice unavailable to our mothers or grandmothers; we could choose, as Anne Helen writes, to “let go of old fashioned ideas of beauty and femininity, embracing your own understanding of what liberation and power looks like…” It was a new brand of feminism for publishers and companies to cash in on. They told us that when it came to our bodies, we could choose different types of women to be.

I, for one, did not take this seriously as an option. I was a fat teenage girl in the early-to-mid aughts, and there was not a crumb of liberation nor power in that experience. Every woman I knew seemed to care about being skinny more than she cared about anything else. Every famous woman admired by girls my age was rail thin. Movies and TV shows regularly deployed fat jokes or positioned fat characters as subhuman buffoons. I suspect all of it had given teen girls of the time well-calibrated bullshit detectors: We were being told “Your body is OK” and “Your body should change” on the same pages, but we were shrewd about which mandate to follow for maximum social acceptance and capital. We knew even then that the medium was the message.

If I’d had the mind or words then to send a letter to the editor of those teen girl magazines bursting at the staples with contradictions, I might have written: You taunt us with this illusion of freedom? You tie us to your bumper and drag us down the highway, but have the nerve to tell us to let go?

Around my mid-20s I started to see more options for what kind of woman I could be.

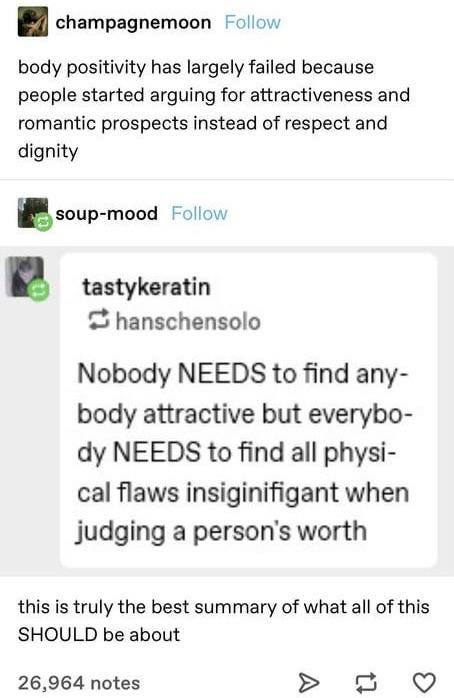

I could choose to be a woman who was unashamedly plus-size, who would never diet again, who was body positive or fat-accepting, or who found her “flaws” beautiful. More people were being these ways, or were at least saying they were. “Love your body — really, this time — and everything will be OK!” seemed the au courant ethos, and it became less acceptable to discuss diet tips, weight loss, or trying to get the tiniest possible butt. This led some people to think that thinness had gone out of style. It had not.

But my old bullshit detector was still blaring. All of this felt like the same “saying it because it’s the right thing to say” lip service of my youth. I was suspicious of the idea that most millennial women were truly able to shed the desire for thinness seemingly overnight; I suspected that they just learned to keep it under wraps to fit the picture of the correct, feminist, progressive kind of woman our forebears couldn’t be. I wasn’t alone — in her 2018 piece for Vox, “Body Positivity Is a Scam,” Amanda Mull wrote:

“Nothing has changed in how most people feel about themselves; instead, it’s simply become very gauche to articulate any of those negative feelings. That wouldn’t be very body-positive of you.”

A millennial woman I know recently told me she wants to lose some body fat leading up to her wedding, and said she hated herself for wanting that. That kind of statement — one I hear often, when women confess such feelings to me as if they’ve committed homicide — evinces the millennial body image curse: We are disappointed in ourselves for not being thin but are also disappointed in ourselves for wanting to be.

Here’s the God’s honest truth: I think I’ll always want to be a little thinner than I am, most of the time. I’ve only not felt that way when I weighed around 15 pounds less than I do right now, which is a state of being that requires me to be working out intensely most days of the week and eating nutrient-dense food 98 percent of the time — no alcohol, no processed sugar, no fun. I don’t always want to live that way, so I don’t, and in exchange I’m a little fatter than I want to be. That’s the exchange I’ve learned to live with. That’s my personal brand of body acceptance. It does not require complete repudiation of my personal ideal; it does not require total purity of thought.

What if it isn’t such a terrible thing to have this nasty little want? What if it’s OK to accept that it exists, as long as we don’t align our entire lives around the struggle for thinness or our self-hatred for not being thin? What if we accept that this desire that was implanted in us is simply a personality quirk? What if we could joke about the ol’ millennial body image bullshit and how it shows up in our thoughts and behaviors the same way we joke about being eldest daughters or having ADHD brains or being Capricorns?1 What if we accepted that we sometimes want this thing it’s not so progressive to want because the things you learn when you’re young tend to stay with you forever? We could relax a little. We could bask in the dizzying relief that comes with radical honesty.

Maybe we haven’t experienced enough personal growth to eliminate the want, and maybe we never will. The self awareness of the issue, though, is the growth. Resenting the want — rather than unquestioningly bending to its whims like we did when we were teenagers — is the growth. The refusal to allow it to consume our lives the way it once did is the growth. And if any of us wants to lose weight, the desire to pursue less damaging ways of doing it is the growth.

If at this point in my life I want to cut body fat to reveal more of my musculature, I’m not going to avoid eating anything but six almonds all day to try to lose 25 pounds in a month. I’m going to take what I’ve learned about total daily energy expenditure and macronutrients and body composition versus scale weight and do it in a sane, safe, sustainable way, like a fucking adult.

Sarah Miller wrote in 2020 that “the material conditions of being a woman have not been altered in any dramatic way, and seem to be getting worse, for everyone.” Perhaps she’s right — the mainstream coveting of thinness is more allowable than it was five or so years ago and we’re being reminded that, as

puts it, “This society fundamentally cannot disentangle health from thinness, wealth, and whiteness.” Unless you gather every ounce of resilience you can muster (not easy), these realities indeed make life difficult.But just as I feel optimistic we can find relief in the acceptance of our problematic little body thoughts, I also feel optimistic about how some aspects of our culture have changed. Even if thinness hasn’t been cast out for good, consider how different media is from when we were teenagers: Mainstream magazines put fat models on the cover and have weight stigma style guides. Fat jokes in television and movies are far less tolerated, and fat people are well-written leading characters whose weight isn’t mentioned at all. Plus-size women are chart-topping singers and models and red carpet hosts. Not-thin bodies have become more accepted and normalized. In adulthood, millennials are looking at a much-improved body culture landscape.

What has not changed is that thinness is still the beauty standard2 for women. I’ve stopped imagining this will change in my lifetime and sleep better for it. I think many people who are lamenting that thinness is “back” are at least partially disappointed that their body type might have had a shot at being considered most beautiful until thinness praise became OK again. For some people, I’m not sure it was really about body acceptance — it was about wanting to be considered beautiful, for once.

Maybe a thin female body will always be the beauty standard. Well, that’s why we should care about beauty less. Maybe not-thin bodies will never be considered the most beautiful and aspirational of all, but it can be enough that they’re … fine. I think we can be OK with looking only OK. That’s part of my personal brand of body acceptance, too.

The millennial condition of always wanting to be a little thinner than we are isn’t yet another thing we must try in vain to optimize or therapize entirely away. It’s so much bigger than us. We carry around this desire because of the influence of the entire media landscape, long-held societal and culture values, and our peers and family members. To deny that those forces have had lasting effects on us to this day is to deny their immense power, and that’s a mistake — future generations will not be spared their own body image curses if we don’t keep our eyes trained on exactly what’s causing them. Millennials are in a prime position to be custodians of that cause. I just wish someone had been doing it for us.

If you liked this post, please share it on Notes, with a friend, or on social media. Click the ❤️ below so more people find me on Substack! And leave me a comment, I’d love to hear from you.

I’m all three of these — it’s an insufferable personality hat trick!

There can be greater acceptance and normalization of a way of being, and it still might not become a standard.

“We are disappointed in ourselves for not being thin but are also disappointed in ourselves for wanting to be.”

So painfully accurate😩

As a millennial woman who’s never been the right size despite being so many different sizes over the years, this is great.